- Home

- Sara Barron

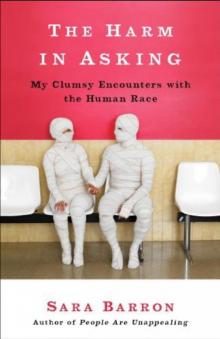

The Harm in Asking: My Clumsy Encounters With the Human Race

The Harm in Asking: My Clumsy Encounters With the Human Race Read online

ALSO BY SARA BARRON

People Are Unappealing*

*Even Me

Copyright © 2014 by Sara Barron

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Three Rivers Press, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Random House LLC, a Penguin Random House Company, New York.

www.crownpublishing.com

Three Rivers Press and the Tugboat design are registered trademarks of Random House LLC.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available upon request.

ISBN 978-0-307-72070-2

eBook ISBN 978-0-307-72071-9

Cover design by Dan Rembert

Cover photograph: Getty Images

v3.1

This book is for Geoff

Contents

Cover

Other Books by this Author

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

PART I: Homebody

1. Scrub Toilet Super-Super (A Tale in Twelve Parts)

2. Bonjour, Delphine

3. The Stupids Step Out

4. Seven Ages of a Magical Lesbian

PART II: Renegade

5. Alcoholics Accountable

6. The Boogie Rhythm

7. The Super Silver Haze

8. Appetite for Destruction

9. Forever Yours, Flipper

10. How Long Till My Soul Gets It Right?

PART III: Roommate

11. Mole Woman

12. Can’t You Help a Person Who Is Sick to Wash Her Back?

13. Not All Italians

14. Eleanor Barron

15. Talk to Her

16. In Defense of Band-Aid Brand Adhesive

PART IV: Survivor

17. Vicki’s Vagina Is Violet

18. This Might Be Controversial

19. Daddy’s Girl Should Wear a Diaper (A Tale in Twenty-Five Parts)

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Part I

Homebody

1

Scrub Toilet Super-Super (A Tale in Twelve Parts)

1. INTRODUCTION

Every week, I scrub the floors of my apartment. The way I go about the chore, personally, is I rip green abrasive tops off kitchen sponges, dampen them with soap and water, and glue them to the bottoms of my socks. Then I start gliding. It all looks a bit like cross-country skiing, which is effective for cleaning, but also exhausting. Once I’m done, I feel I deserve a treat. More often than not the treat comes in the form of a medical miracle show on TLC. This week’s episode was about a legless dancer and recent Juilliard graduate. Asked about her personal triumph over adversity, she stared squarely into the camera.

“Here’s what you do,” she said. “You dream. You believe. You achieve.”

“No, you achieve,” I corrected. “I do not achieve. Juilliard won’t let me spin on stumps instead of pointe shoes.”

For years, I’ve been jealous of the ailing and deformed: quadriplegics, human mermaids. A girl with organs on the outside. I don’t crave the impairment, really, I just think the attention seems nice. And this puts me in the minority. Murmur, “That looks fun,” at the sight of conjoined twins, and learn, ironically, what it means to feel alone.

2. MY SON HAS ASTHMA

Allow me to defend my position by explaining how I got here. You’ll like me more that way.

When I was ten years old, my six-year-old brother, Sam, was diagnosed with asthma. This diagnosis was the stone that built the fountain, and it was from this fountain that a neediness would spring. It wasn’t hope that sprang eternal. It was an aspiration for attention, the desire to feel special and unique.

Sam’s diagnosis wasn’t good news per se, but neither was it without its benefits. For it would gift unto my mother the eventual guiltless employment of a maid. And also a motto:

My Son Has Asthma.

Like most ineffective plans for coping, it emerged the day of diagnosis. I’d gone to visit my brother in his hospital room, where he lay ensconced amid festive pillows and Mylar balloons. My mother sat perched at his bedside massaging his scalp. The attending nurse breezed through. She fluffed Sam’s pillows and saw me sitting in the corner.

“Wow!” she said. “In that polo shirt, you look just like Jerry O’Connell!”

It was 1989. Jerry O’Connell was not yet the strapping, chiseled husband of Rebecca Romijn, but rather the rotund child star.

The nurse departed. I said, “Mom. That nurse said I look like a boy, and that I am fat,” and my mother, still massaging, turned impatiently toward me.

“Not now, Sara, please,” she said. “Your brother Sam has asthma.”

Sam was already buoyed by a virtual raft of gifts. He was getting a massage! He was going to be fine. This whole asthma situation looked awfully good from my vantage point and a moment or two devoted to my own problems was, I thought, a fair thing to ask.

I considered throwing a tantrum. However, my mother preempted my tantrum by suggesting a stroll down the hallway.

Sam and I agreed. Sam had energy to burn from all the ice cream he was getting. As for me, I hoped to run into a boyishly handsome nurse who would say, “Sorry to bother you, but I simply had to ask: Are you Tina Yothers? You two look exactly alike.”

Sadly, the only person we ran into in the hallway was a sickly old man. He was balanced against a wall so he could let go of his cane and eat a Danish. He was blocking our path, and the fact of this had pissed my mother off.

“Look out!” she yelled. “Please: My son has asthma!”

The phrase became a generic exclamation, an oy vey stand-in employed to express varying emotions: Exhaustion, fear, surprise. Disappointment, foreboding, resolve.

Here, a sampling of occasions and the uses they’d inspire:

A hot day: “The humidity! My son has asthma!”

A long line: “This wait! My son has asthma!”

A casual dinner with friends: “Carol, pass the antipasto platter, please! I have a son with asthma!”

MY BROTHER RETURNED home after three days in the hospital. In an effort to keep his asthma in check, my mother fed him hyperactivity-inducing steroids chased with hysterical advice, including but not limited to, “You’ll die if you smoke a cigarette” and/or “You’ll die if you stand near a lit cigarette.” The other order of business was to ensure a dust- and allergen-free home, and it was for this reason that my mother, for the first time in her life, decided to hire a maid. She’d dreamed of doing so for ages. We all had, as a matter of fact, since being near my mom when she cleaned guaranteed that you, whoever you were, would get to push her martyr button. You’d be minding your own business, for example, braiding your arm hair, when suddenly she’d have you by the wrist to coax you back behind a toilet.

“What do you see back there?” she’d ask.

“It’s very clean,” you’d answer. “So … nothing?”

“Nothing but …?”

“Nothing but … evidence of how hard you work?”

“I slave.”

“Nothing but evidence of how hard you slave?”

“Exactly.”

The guilt my mother associated with hiring a maid floated away on Sam’s first grating wheeze.

“I wish I didn’t have to have one,” she’d say about a person, like a person was an enema. “But I do, of course. I have a son with asthma.”

3. WITAM IS POLISH FOR “HELLO”

The following Monday a van pulled into our driveway. A woman climbed out and walked toward our front door. This w

oman was truly enormous. I never did measure her for fear she’d slap my hand off, but my guess is that she measured in at a healthy six-foot-one. She entered the house, and it was only then that I noticed the smell. It was as though she’d smeared herself in salmon, then thought, That was stupid, and then smeared herself in Pine-Sol.

“Al-oh,” she’d said, in what I’d soon learn was a Polish accent. “I am Wanda.”

“Witam, Wanda,” said my mother. “I am Lynn. Lynn the missus and the mommy. Witam, witam.”

4. FOREIGNERS APPRECIATE THE EFFORT

My mother spent a portion of 1968 on a kibbutz in the company of an Israeli boyfriend named Yoni with whom she spoke Hebrew. The experience left her with the impression that she had a knack for language, and now, with a chance to test the theory, she’d spent the afternoon prior to Wanda’s arrival riding her stationary bike, poring over a Polish-English dictionary.

“It’s my way of reaching out,” she said. “Foreigners appreciate the effort. I know these things. I traveled before I had you, you know. And before I had a son with asthma.”

5. WANDA GO MUNCH-MUNCH

A house tour commenced between my mother and Wanda. With nothing better to do I trailed along behind. I listened as my mother used the occasional bit of Polish. There was da (yes) and nie (no), as well as the more complex nie spóznij (do not be late) and nie ukrywam moje pieniadze w moim domu (I do not hide my money in my house).

As for the bulk of their communication, it was a language of their mutual invention. Watching it unfold was not unlike watching a lovers’ waltz, the coming together of two halves of a whole. You can’t put a price on chemistry, see, and these two shared a wavelength. Call it kismet. Then tell me this is easy to decipher:

“Go here for a vroom-vroom, yes? BSHHHHHHHH? Dusty dirty go gone!”

That’s what my mother said to Wanda. And presume what you will, but Wanda did not respond, “Missus! Stop! You embarrassing you!”

No. She rather nodded like, Thank you, Lynn, for showing me the vacuum in the closet.

“BSHHHHHHHHH!” Wanda shouted. “Dirty go gone!”

“Da!” said my mother, and nudged Wanda toward the kitchen, where a plate of Triscuits sat on the counter alongside a hunk of cheddar cheese. My mother pointed at the cheese and crackers, and then at Wanda’s stomach. “It goes GRRR? Wanda go munch-munch.” She mimed feeding herself. “Okay, okay?”

Wanda nodded. “Yes. Okay.”

They proceeded upstairs to the bathroom.

“One toilet?” asked Wanda. “One for the mister and the missus and the babies?”

“One bathroom, yes,” said my mother. “Lynn no a fancy lady, Lynn house no so fancy. See the toilet?”

“Da. I see you toilet.”

“Okay. Toilet yucky-yucky. So you scrub toilet super, Wanda. You scrub it super-super.”

Wanda launched her sternum toward the toilet to pantomime aggressive scrubbing. “Super-super missus, yes?” she asked.

“Oh, yes,” my mother answered. “This missus tells you: Yes.”

The house tour concluded with a conversation on the subject of Sam’s asthma. My mother called to Sam in his bedroom, and out he came, trotting along. She positioned him such that his back was to her and his face was to Wanda.

“Wanda,” said my mother, “here is Baby Sam. If home is dusty dirty, Sam go, ‘Hack, hack.’ Dusty dirty bad for Sam. You no scrub super-super all the home, Baby Sam is …” She performed wheezing. She made a woo-woo noise like a siren. “Baby Sam to doctor. BABY SAM AT DOCTOR BAD!”

Wanda gave a solemn nod. She pointed a sizable finger at my mother. “You a mommy,” she said.

“Yes,” said my mother.

Wanda pointed back at herself. “I a mommy.”

“Yes,” said my mother.

“I a mommy. So I know: Mommies suffer for the babies. MISSUS SUFFER FOR THE BABY SAM!”

Indulgence, as a quality, is too winning to let go. By the time Wanda left later that afternoon, my mother had already booked her services for all forthcoming Mondays.

6. THE PUBE PROB (OR “THE PUBERTY PROBLEM”)

After a month of Wanda’s weekly visits, I developed a habit of locking myself in the bathroom.

My actions were prompted by Wanda’s cleaning style, which was aggressive to the point of feeling competitive. The verbs “attack” and “stampede” jump to mind; she would attack one room and stampede into the next. Broadly speaking, the seriousness with which Wanda took her professional duties was to her credit. But as a ten-year-old on the cusp of an early-onset puberty, I found her diligence annoying. Eventually, I found her annoying, for I was in a life phase that included quite a bit of pelvic thrusting. Pelvic thrusting of varying, well, pelvises: my pelvis, the pelvises of my dolls. And it was as though Wanda had some sort of motion sensor planted somewhere in that strapping frame of hers, and any pelvic motion set her off. Consistently, she’d stampede into my bedroom to find me mounted atop … well, just go ahead and pick your poison: throw pillows, beach balls, felt hats. The list is long. So it was that a door with a lock became a top priority. I holed up in the bathroom because it was the only room that had one. And, thankfully, because Wanda was finished with it by the time I returned home from school. It may have been small and it may have lacked a television set. Nonetheless, it was private and available. My pelvic activities being what they were, these aspects were important.

7. THE PRIVE PROB (OR “THE PRIVACY PROBLEM”)

Over time, a weird thing happened. Locked in the bathroom, I invented imaginary friends to keep me company. And if you’re thinking, That’s not weird. It’s what kids do! I’ll point out that I had no fewer than three, and that each one of these three was accessible to me only after I’d taken a shit.

It started out as a Monday-only thing. It became the entirety of my prepubescent life.

There’s a percentage of my adulthood I frankly should’ve spent wising up on politics that’s rather been devoted to unearthing the rationale behind all this. As an adult, I put a therapist on the job, and she stroked the old gal’s ego by suggesting it was the byproduct of my intuitiveness. As in: a conversation with a nonexistent person works best if it’s in private. Smartly I sensed this, and so grouped it in my head with another equally private activity. I was VERY AWARE as a child. You see the self-flattery there? It’s way far up my alley. As such, I thought I ought to roll with it.

MY MONDAY ACTIVITY schedule, Age Ten:

3:30 p.m.: Arrive home, fetch granola bar, head to bathroom.

3:35 p.m.: Arrive in bathroom. Lock door. Eat granola bar.

3:40 p.m.: Random activity of choice, e.g. inspect mole, lie in empty bathtub pretending it’s a sun-bed.

4:00 p.m.: Shit.

4:01 p.m.: Chat with imaginary friends.

5:00 p.m.: Listen for Wanda’s departure.

5:01 p.m.: Confirm Wanda’s departure.

5:02 p.m.: Wipe ass. Flush toilet.

5:03 p.m.: Unlock door. Depart bathroom.

I named my imaginary friends Nancy, Jenny, and Kelly. They were all orphaned teen models, and I’d been put in charge of caring for them after having been deemed a prodigy in the field of adolescent education. We all lived together in a pretty Victorian mansion. It was an imagined compilation of both (a) a Barbie Dream House, and (b) something I’d seen on a family vacation to Newport, Rhode Island.

It had a front porch, too, our mansion, that I’d extracted from a Country Time Lemonade commercial.

I was doted on and greatly admired by my orphaned teen models. They craved my advice on everything from boys to needlepoint to who among them had won a game of gin rummy. They were exhausting but rewarding, and in exchange for my wisdom, spent a large portion of their free time showering me with attention. They discussed my exceptionality in the areas of intelligence, acting, singing, dancing, flexibility, and improv. They told me I, too, could be a teen model.

“Really?” I’d ask. “Modeling? You think?” and Jenny w

ould answer, “With a bod like yours? Oh yes. Just give it time.”

The personalities and circumstances surrounding Nancy, Jenny, and Kelly suggest a sharp eye for twenty-first-century television. I intuited the basic constructs for both Sex and the City and myriad reality shows before either even existed. À la Miranda, Samantha, and Charlotte, my imaginary friends were divergent in both their interests and dimensionless personalities. Nancy was passionate about good manners and landscape painting. Jenny enjoyed male chest hair, sex, and makeup. Kelly liked kickball and swearing. Additionally—and in the vein of reality shows from America’s Next Top Model to the old Diddy classic Making the Band—Nancy, Jenny, and Kelly passed the time in an expensively decorated home engaged in inane conversations, waiting to hear from the God-Figure (e.g., Diddy, Tyra Banks, me) about their next scheduled outing.

Confine the idiots, goes this philosophy of entertainment. And wait for disaster to strike.

8. ENTER GOLDSCHMIDT

I was in a bad mood after a particularly draining Monday. A fourth-grade peer by the name of Becca Goldschmidt had tugged at the ill-fitting underpants I’d had on. To be fair, they had been bunched visibly beneath my stretch pants so as to resemble an untended dump, and very much begged for the plucking. So Becca Goldschmidt plucked. Fine. What I took issue with was that then she went the extra length of shouting to no one in particular, “SARA BARRON’S BUTT IS DISGUSTING! SARA BARRON’S BUTT IS DISGUSTING!”

“So what?” I yelled back. At which point Becca Goldschmidt shouted, “Oh my God! She knows her butt is disgusting!”

The Harm in Asking: My Clumsy Encounters With the Human Race

The Harm in Asking: My Clumsy Encounters With the Human Race